Truth IS Stranger than Fiction

“The reason that truth is stranger than fiction is that fiction has to have a rational thread running through it in order to be believable, whereas reality may be totally irrational.”

— SYDNEY J. HARRIS

If you’ve been following me for any length of time, you know that I’m an advocate for using words to heal. Previously, I’ve talked at length about expressive writing, journaling, and non-fiction as a way to harness the power of words (I even have a course about it!). But I’ve spent the last few years sitting on this idea of writing fiction to heal. Why?

It’s hard to translate how powerful it can be without tangible examples and guidance. And also, to be honest, I’m not a fan of other writers/authors telling people how to write. I’ve been in the writing industry a good while now and one of my biggest pet peeves is when someone tries to sell others on their “method” of writing, claiming it’s the “best” way or the “right” way.

There’s so much… noise. I didn’t want to add to it.

But then I realized that there was a way to teach and convey this concept to people without having to be one of “those people” that annoy me. I could share what I believe to be a very powerful approach to writing without having to “sell” it as some tried and true method (because it’s not).

That’s why I created my Writing Fiction to Heal Experimental Workshop & Community. Because it’s less about dictating a certain way to write fiction and more about leaning into the power of words, truth, and fiction to discover how it can help us heal as individuals.

Think of it as a social experiment.

Because that’s pretty much all life is. One giant experiment that we’re all trying to “figure” out. It’s also how humans learn best. We try something. It doesn’t work. We try again. It still doesn’t work. We try, yet again, and hey, a little progress!

Those who join are in are on the experiment with me. We’re all going to be learning what concepts and parts of the process work for us collectively and individually. But we get to do it together. With compassion and support.

Maybe I’ve got your attention now and you’re wondering — okay, but how?

Valid question. And over the next few weeks, I’m going to answer it. Today, though, I’ll start with two super easy reasons that writing fiction can be a perfect place to start the healing process.

BECOMING A CON [WO]MAN

“Every decent con man knows that the simplest truth is more powerful than even the most elaborate lie.”

— ALLY CARTER

Good fiction, like any good con, is steeped in reality. What writers and con-artists share is the ability to take the truth and twist it into a story worth believing. And the best con-artists/writers start with what they know best: their own reality and truth.

That’s why the oft-dismissed phrase, “write what you know” is actually good advice in my opinion, though often misused or misrepresented. It’s often given to new writers on a surface level, unexplained way. Taken at face value, I could argue that because I know a lot about cats that I should, therefore, write about cats.

Just kidding, but not really. No, I shouldn’t write about cats because I don’t think that’s what the advice really means.

It’s my very humble opinion that “write what you know” means approaching the page with what you know to be true about the emotions, desires, goals, motivations of the character or scene.

So how does this relate back to actually writing fiction to heal?

Well, let’s look at an example.

Let’s say that Jane Smith is wanting to work through one of her real-life struggles of conflict/confrontation. She decides to write a scene where her main character (protagonist who is very much like Jane) has to confront her horrible boss (antagonist who is very much like her stepfather). They are having a conflict that has nothing to do with the conflicts in Jane’s real-life, but through the use of her fictional scene, Jane can make her character explore things that Jane isn’t ready or willing to. She can make her character do or say things that Jane normally wouldn’t or on the flip side, she could make her character do the things that Jane wants to do. She can “try it on” for a bit and see what she thinks.

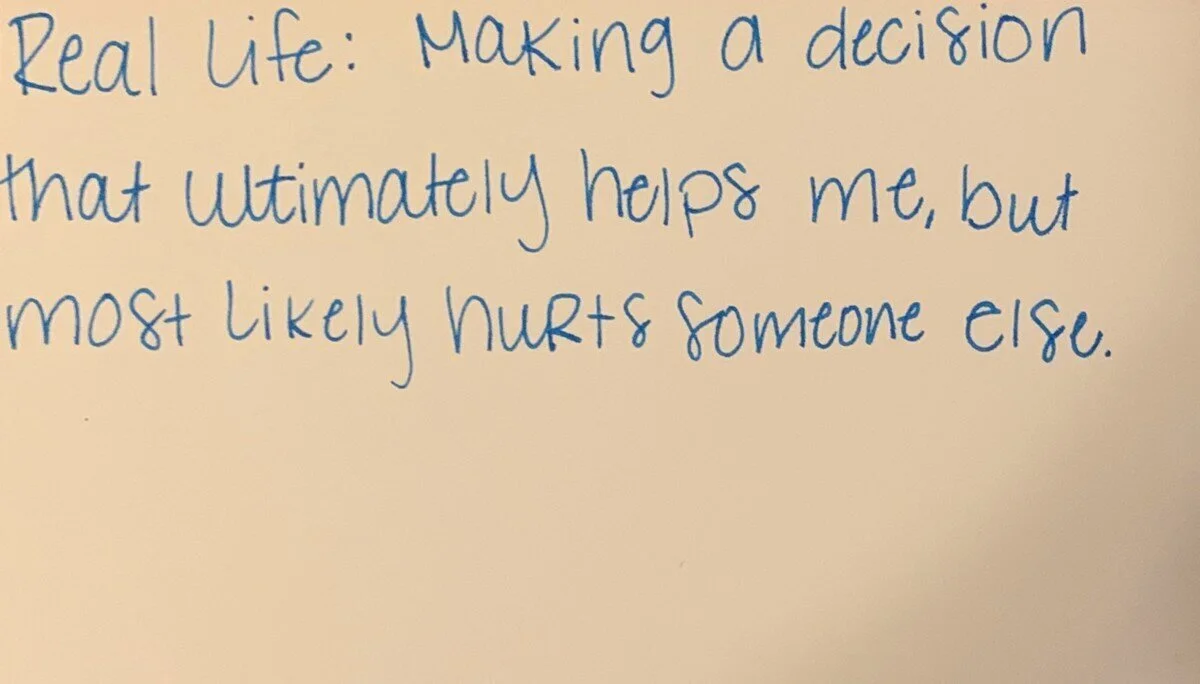

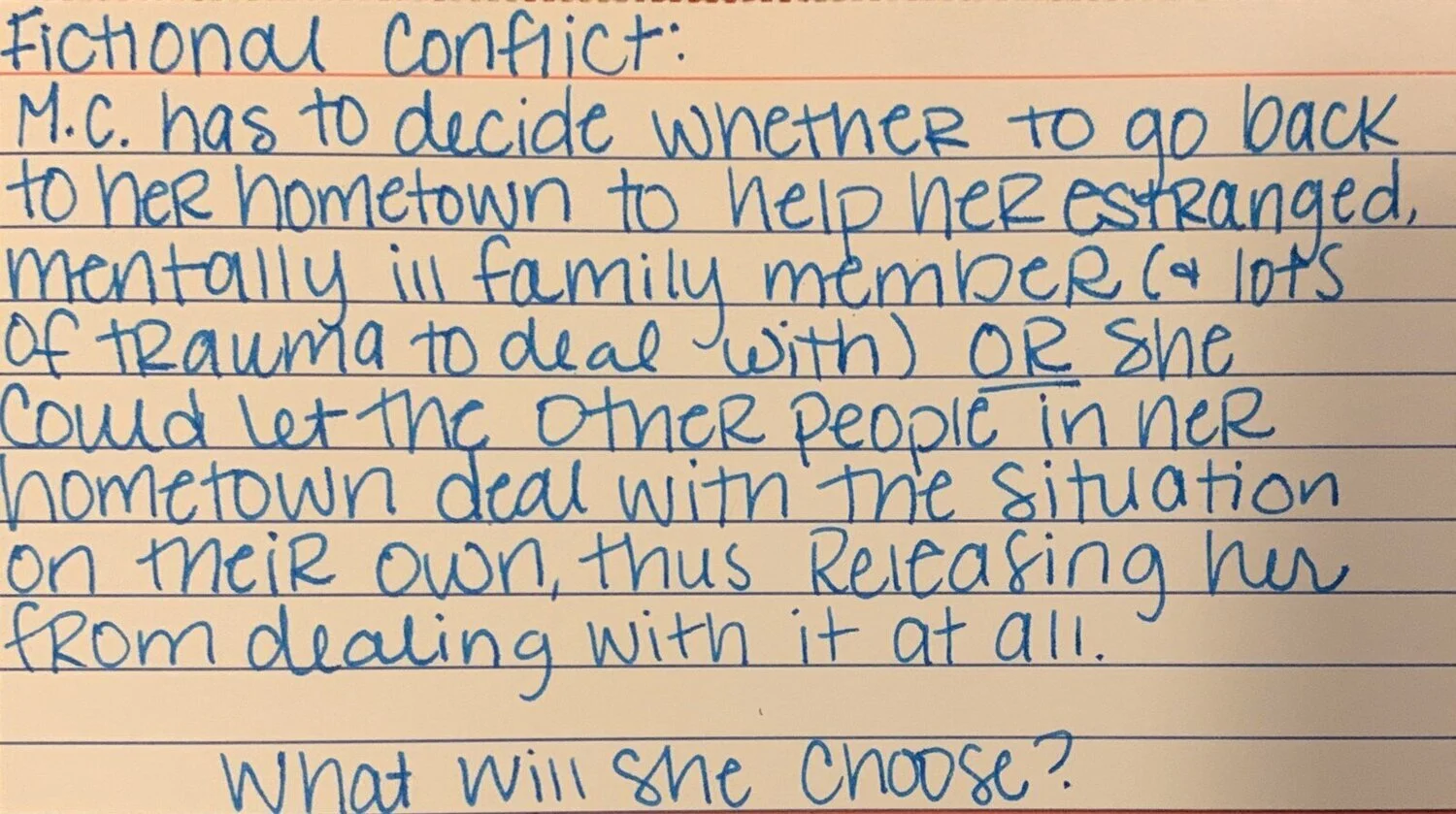

Here’s a real-world example of mine from a few months ago:

Note: the fictional conflict was not in any way like my reality, but at the heart of that conflict is the same type of emotional decision I was facing in my real life. Had I actually written that fictional conflict, (I literally have hundreds of notecards like this. Possibilities for future novels are endless!) I could have explored the emotions I was facing by using the main character. Would my character make the same base decision as I would? Would the person(s) on the other side of her decision feel the same way the person I was facing my real-life conflict would?

So you see, the emotional truth is at the root of every single story ever told. Sure, it may be disguised or wrapped up as something else on the surface, but beneath the weight of ink and paper (or an e-ink screen) is the truth… waiting to be uncovered.

ASKING FOR A FRIEND

You know those situations where someone really wants to ask a question to help their own situation but they don’t want to admit that it’s actually for them? It’s the whole “asking for a friend” approach. Fiction offers us that emotional distance to explore things we’re not quite ready to explore in real life.

For example, let’s say Jane Smith isn’t happy in her marriage and has been questioning what to do. She isn’t ready to talk about it with family or friends, yet. She decides to write a fictional story where the main character actually goes through a divorce. Through her research for the character (and ultimately herself), plus pouring her emotional baggage into the character, she realizes that divorce isn’t actually the answer for her. By exploring her own emotions, desires, questions through her fictional characters, she was able to uncover that what she really wanted in her marriage was a deeper connection with her husband. This gives her the confidence to take steps toward approaching her husband with ideas to improve their relationship. Of course, this is a positive result of her work with fiction. On the flip side, through her research and the emotional war on the page, she may actually realize that she does want a divorce and working through that fictional situation may give her the confidence to approach it in real life.

The point is — when you ask the page a question you can’t ask in real life, there’s a very big possibility you will find the answer.

Writing fiction to heal isn’t all that straightforward but that’s precisely why art often imitates life.

If you’ve been searching for a low-risk, high-reward, and affordable way to explore your past trauma or deep emotional questions— you have nothing to lose by giving fiction writing a chance.

Sounds interesting, but not sure how to put it all together?

No worries, that’s exactly why I created the Writing Fiction to Heal Workshop — I encourage you to check it out.